Monsters

by Ashley Wilson

In either movies or books, a well-presented monster will always win me over. Dragons are my favorite, vampires next, followed by any manifestation of a creature of the deep, then aliens. In my opinion ghosts and paranormal activity do not really count as monsters, and werewolves are just okay; You can try to change my mind on this one, but I have yet to encounter a truly convincing werewolf shapeshifter narrative. Plus, I’m not too keen on the howling.

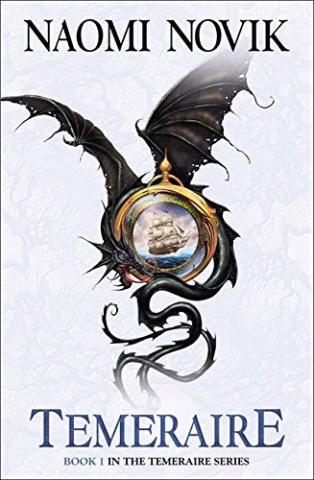

Dragons take the top prize for me because regardless of their assumed or presented size, they never fail to capture the imagination. “Temeraire” by Naomi Novik is a fan favorite alternative history featuring a Captain serving in the Royal Aerial Corps with a dragon as his preferred form of flight. The wyverns in Sarah J. Maas’ “Throne of Glass” series are both clever and fierce, but lend a tenderness to their otherwise course riders. Then of course there is the glorious Smaug, brought to this world by J.R.R. Tolkien and presented in both book and film series, “The Hobbit.” If by chance you have not yet met Drogon from “The Game of Thrones” series—birthed by fire and sacrifice along with his siblings Rhaegal and Viserion and one of the most terrifying dragon manifestations to date—please start reading or watching this series as soon as you are able.

In all formats of entertainment monsters serve to provide hope, tragedy, salvation, reincarnation, and fear. They are excellent vessels for symbolism. Sometimes the monsters can serve as the hero as in Anne McCaffrey’s “Dragon Riders of Pern” or “The Inheritance Cycle” by Christopher Paolini. The monsters might be purely selfish like the Kaiju in Guillermo Del Toro’s “Pacific Rim” or Pan in his relentless tasks set to capture his princess in “Pan’s Labyrinth.” In other stories a monster may be the only of its kind, the line of morality blurred as humanity grapples with its own meaning of existence. A number of the “Godzilla” films and Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” use loneliness as a marker of the monster’s emotional experience, and Devil Dinosaur from the Marvel comic “Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur”, would be very much alone in his monsteriness these days if it wasn’t for the mental link that he shares with the smartest inventor to date, young Lunella Lafayette.

The morality of monsters can also be set by their origin stories, giving the reader/viewer a glimpse into what may become of humans made immortal. Enter the vampire. Some vampires have caring mentors who wish them to be righteous vampires like Carlyle in “Twilight.” Others are born out of bloodlust or loneliness like Victoria’s army from “Twilight Saga: Eclipse” and Claudia from “Interview with a Vampire.” Since vampires begin as humans, their choices and morality have plenty of avenues. In “True Blood” the vampires are after money and power, and in “Only Lovers Left Alive” there is love and music. “Blade” is a half-vampire who seeks revenge on those who prey on humankind, and in “What We Do In The Shadows” the viewer gets the sense that the vampires exist only to indulge in dramatic self-infatuation.

Sometimes in stories there can be monsters of more than one kind. In “Lovecraft Country” and in “The Watchmen,” monsters can serve as a comparison or contrast to ourselves and our actions too. They act like a mirror. We are left reflecting upon whether or not the humans in these stories are supposed to be better or worse than the monsters they create.