Lost and Found

by Seth Warburton

It is not usually a pleasant task to clean my workspace, digging through the detritus of recent projects, notes from decades-old committee work and only then down to the worktop. This time, however, I made an interesting discovery. Tucked in a moldering folder in the back of a hand-me-down file cabinet were the papers of my predecessor’s predecessor, including an unpublished draft intended for this very column. Thinking that this discovery would be of interest to readers (of the Ames Tribune and of books alike) here is the work of librarian Karel Naaktgeboren who retired from the library in 1987, at age 81:

Frame: In English usage via an old Germanic word meaning “to be useful.” Appropriately enough, one modern meaning is a structure useful to build more work atop. A frame could be the scaffolding which holds up a house, or it could be the few thoughts upon which hang a new idea. Many novels, too, have frames, those small conceits which allow authors to build grander stories upon them.

This is no modern invention. Think of Scheherazade, whose own story results in the telling of the tales that make up “The Arabian Nights.” Indeed, the story of Sinbad the Sailor, sometimes included in the Arabian Nights, comes with its own frame story of an elder Sinbad relaying his early adventures to a workman (also named Sinbad) on the streets of Baghdad. This results in the highly amusing doubled-framing of Scheherazade telling the sultan the story of Sinbad telling Sinbad Sinbad’s stories! All that to simply relay a tale to the reader.

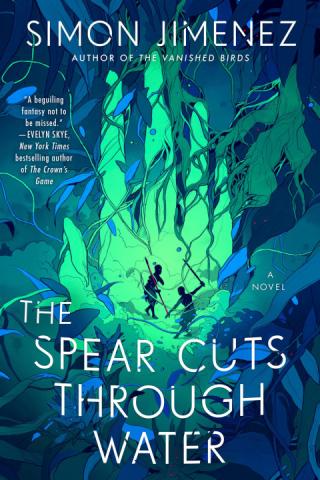

Similarly multi-framed is author Simon Jimenez’s “The Spear Cuts Through Water.” The story of an ancient rebellion against a terrifying emperor is relayed to the narrator sometimes by their grandmother, and sometimes as a performance in a dream-like theater. Most interestingly, these frames threaten to collapse as the past and present draw closer together.

My favorite, and most ingenious, of all the framing devices are books written as if they are historical documents found in some attic or forgotten archive, and hence published. These novels generally cast the true author in the role of discoverer or editor of the purportedly found text. James McBride, for example, presents his National Book Award winning novel “The Good Lord Bird” as the contents of several scorched notebooks found in a church basement which describe the life of a liberated slave’s travels with John Brown. For the finest frames in literature, come to the Ames Public Library.